I Don't Know

This post is adapted from last week’s Frankly video titled “The Three Most Important Words We’re Taught Not to Say.” In the future, we’ll be adapting more Frankly videos to written versions and continuing to post them on Substack, so stay tuned for more.

As a podcast host, there’s one answer that I love to hear when I ask my guests a question – but I rarely ever do:

I don’t know.

To me, this answer is a signal of maturity, nuance, and honesty. It’s not trying to give an answer to all the world’s problems.

So, why is hearing “I don’t know” so rare?

We are all members of a social species embedded in a modern culture that’s been turbocharged by energy surplus and social technology. But in this modern setting we still seek status and respect as a product of our evolutionary wiring. Because of this, in most public settings, especially in the media, we overvalue confidence, bravado, and certainty. Today, saying “I don’t know” is seen as a sign of weakness, not of wisdom.

But in a world increasingly defined by ideological debates, when you hear these words today, they act as a sort of antidote to our cultural consensus trance. Admitting uncertainty makes room for discourse and the possibility of different answers.

In fact, I’m beginning to think that the reluctance to express “I don’t know” (or its equivalent) out loud is a fatal flaw in our culture as we begin to discuss our vastly complex, risky, and rapidly approaching future – which is chock full of uncertainties.

The Right Answer on Wall Street

So back in the day, over 30 years ago, I started working at Salomon Brothers, which at the time was one of the coolest places on Wall Street. Their highly respected training program kicked our asses, and one of the key things I remember is that they would ask a series of questions, starting with something simple that you learn in business school like, “What’s the duration of a 30 year note?” Next, they would ask a slightly harder question: “What’s the ticker symbol of Yahoo?” Easy!: YHOO.

And then, after you answered the first two questions, they would ask you a really hard question that you weren’t supposed to be able to answer. Since we want to impress our bosses, we would inevitably make something up or guess, and then they would come down on us hard.

What we were supposed to say, as eventual salespeople who would be talking to billionaires and institutional managers, is “I don’t know, but I will find out and get back to you.” Because making up answers may sound good on the surface, but doing so would only cause more problems and make us appear incompetent when they turn out to be wrong later.

That concept was drilled into me in my early 20s. But, in the intervening 30 years, I’ve noticed that “I don’t know” is rarely spoken, at least publicly. Our culture doesn’t merely tolerate and accept overconfidence, but actually prioritizes it – and we end up paying a premium for it.

We see this as social media feeds boost a really bold claim, which then goes viral, while the more accurate and nuanced one gets minimal views. On TV and in the news, producers book guests with crisp and sharp takes, not the careful, qualifying one. Even in choosing guests for this show, I lean towards the articulate, confident, charismatic spokesperson for topics over the best scientist. In classrooms the quick hand beats the methodological thinker – and I know this because even in third grade I had the fast hand! In boardrooms and C-Suites, it’s the fast, confident answer that outshines the humble hypothesis. Our modern status economy runs on conviction and linearity, while nuance and caution only slow us down.

Why does this happen? Well, there are three – at least three – intertwining reasons why confidence and lack of humility rise to the top in our current culture.

Three Levels of the Confidence Game

Uncertainty is Stressful

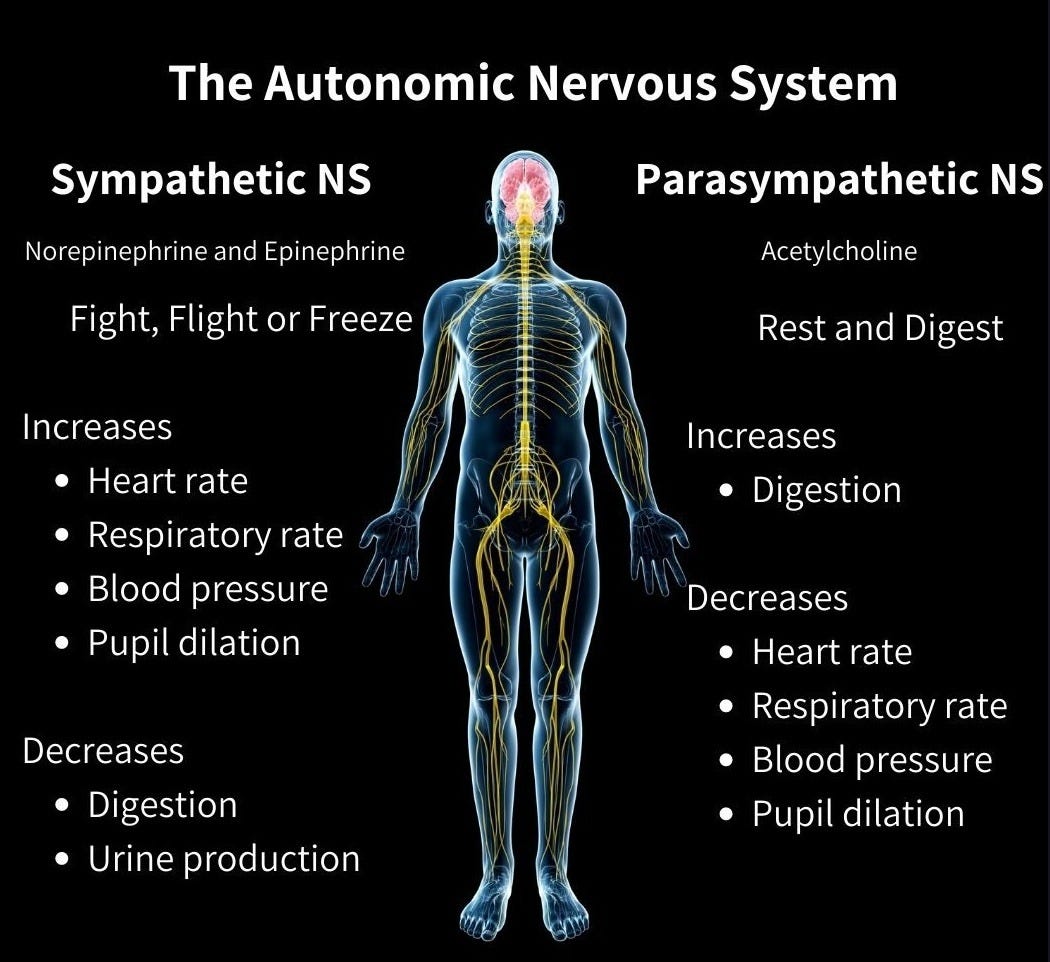

First, at the physiological level within an individual, uncertainty itself actually feels bad. Most of us don’t really think about it, but uncertainty is reflected as a bodily state within us. Human brains are extremely good at predictions: we’re always guessing what’s going to come next and then checking that guess against the reality in front of us. When the world becomes more chaotic, these prediction errors spike and kick in our sympathetic nervous system, what we might call our “bodily alarm network”.

So when our stressed system releases cortisol and we start to feel things like a tight chest, a fluttery stomach, or an increased heart rate, these inform our gut that something is ‘off,’ even before we can really explain why.

And furthermore, being uncertain – by definition – occurs when we build multiple mental possibilities and hold them all at once. In a literal sense, the added complexity of doing this requires more energy for our brains in the form of glucose. Holding uncertainty is costly!

When we’re running parallel mental scenarios, inhibiting quick answers and requiring more context flip-flopping, our bodies don’t like the inefficient use of energy. As this stress increases, our bodies push us to pick some story – any story – to shut the alarms off.

Back in the day on the plains of Tanzania, this response was evolutionarily helpful. For instance, it was safer to assume the rustle in the bushes was a lion rather than the wind, because it was better to have a false alarm over a fatal pause (or maybe fatal “claws”). This translates into today, where modern society continues to reinforce this by rewarding decisive signals over caveats, resulting in “I don’t know” feeling like a professional status risk.

Put that all together, and at the level of the individual human physiology, uncertainty feels both uncomfortable and potentially costly. So it’s no wonder that fantasy and doom often become our default perspectives, rather than sitting with the unknown and being open to learning.

Motivated Reasoning

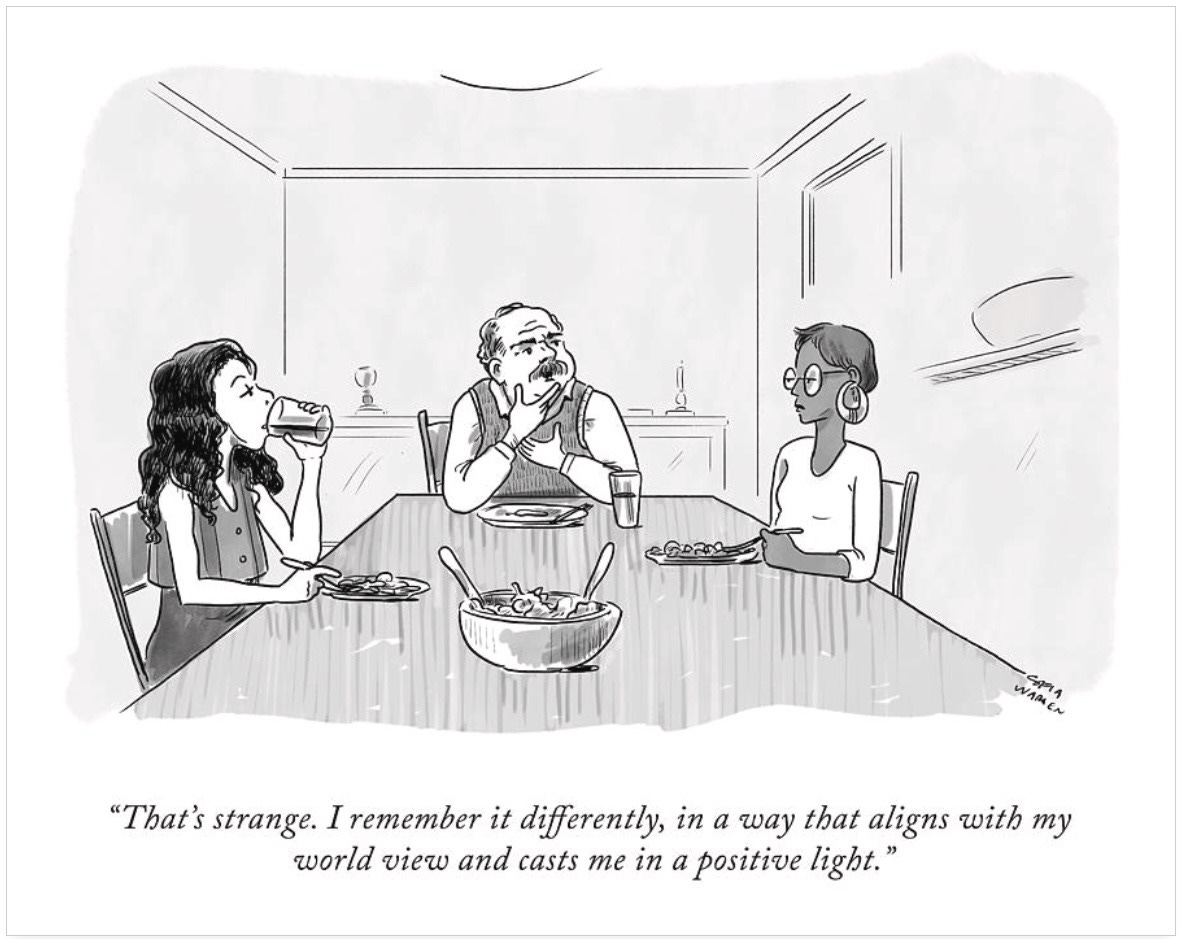

Building on the individual bodily reaction, once beliefs are formed at a higher level, they develop antibodies that make us resistant to change. This is called an ideological immune system, and we all have one. Once a worldview works for us we defend it.

Importantly, a lot of modern research shows that the ‘smartest’ among us are often better at arguing their own side, but also more likely to double-down on their beliefs on highly charged and divisive topics. This tells us that smart people aren’t necessarily right more of the time, but they are better at rationalizing their own positions. This is called motivated reasoning, and it’s very effective at preserving our personal blind spots.

Authority Bias

Moving another layer above, we have culture-wide human cognitive phenomena like authority bias (among many other biases).

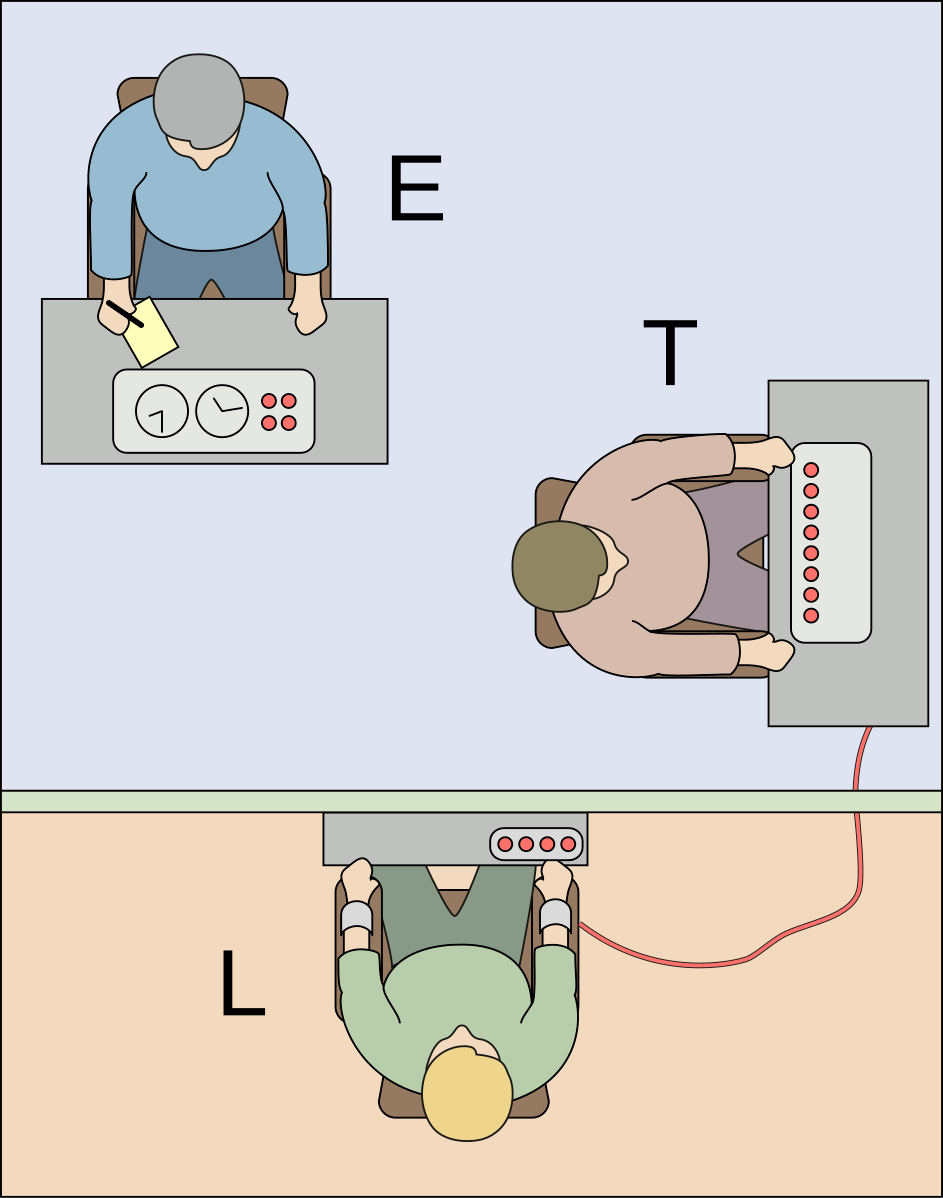

Authority bias is our built-in tendency to trust and comply with people who display signals of high cultural status – titles, uniform, and expert credentials – despite contradictory evidence showing they shouldn’t be trusted. This human tendency has been demonstrated over and over again. Famously, in the Milgram experiment, ordinary people kept delivering what they thought were painful and nearly fatal electric shocks, just because the person telling them to do it was in a lab coat. Another classic field study set in a hospital showed that 95% of nurses prepared an excessive, unauthorized medical dose based solely on a stranger’s phone order because they were claiming to be a doctor – even though the rules forbade it.

Many other studies have repeatedly shown that humans are more likely to obey requests from persons with perceived authority. These examples are all from different settings, but they show the same pattern: signals of authority lower our skepticism, and they raise our compliance. This might not seem surprising, but it does help explain why a lot of us tend to go on autopilot at times when we probably most need to be thinking critically.

This pattern also partially explains why ‘misinformation’ works so well - it’s easy for companies to throw money behind a confident spokesperson to promote an unscientific campaign that’s good for business.

We Want Our Leaders to Have the Answers

From a cultural perspective, we can see why people in authority rarely say, “I don’t know,” because if they did, they’d be replaced by another person who could give an answer and seem to better know what they’re doing. Basically, confident guesses rise to the top, and culture-wide – almost as if by compulsion from what I refer to as the global economic super organism dynamic – we have learned to speak past uncertainty, round off any error bars, and, ultimately, act first confidently and check later.

These incentives shape the outcomes we see around us. Projects start with rosy baselines and then invariably end up with cost overruns. Politicians will campaign on certain guarantees and then walk those promises back when they’re elected and actually have to govern. Even in science, publication bias reduces the chance that statistically insignificant results get published, skewing the body of evidence. So overconfidence in our culture is rewarded at the front end and only punished, if at all, in hindsight – which means the person who benefits is rarely the person (or culture) who pays. The public pays in trust, money, and time. To those who follow TGS, it’s also obvious that our planet pays (and ergo we also pay) in the form of ecological stability.

Enter: Artificial Intelligence

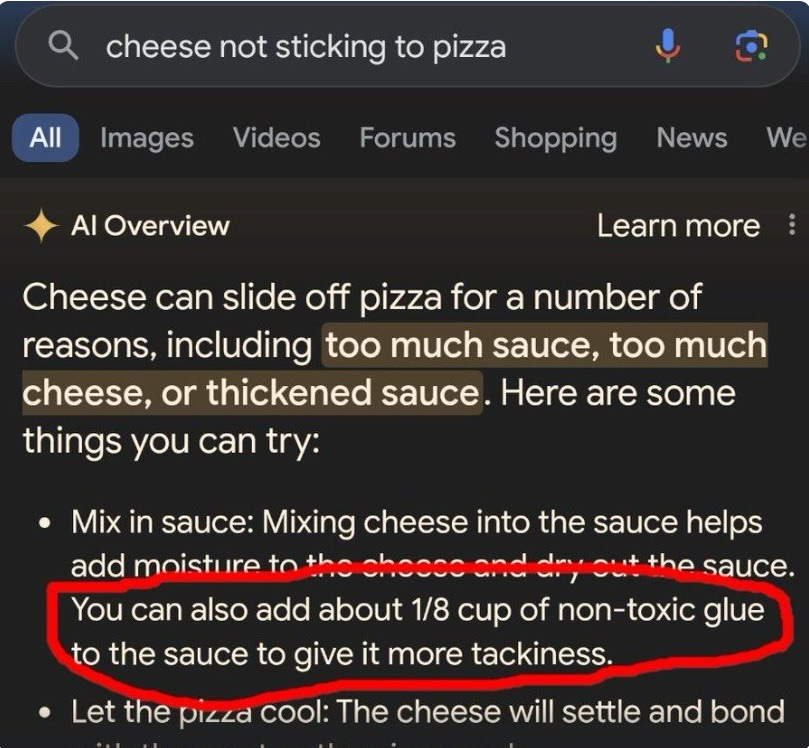

Artificial Intelligence adds a relevant wrinkle here, because it also rewards confident responses, turbocharging what is already a human tendency – which naturally makes sense because humans created AI.

Most people who use AI have heard of the concept of hallucinations. This is when a large language model confidently generates an answer that isn’t true.

The main software of ChatGPT-5 hallucinates around 10% of the time when it has internet access. But without internet access, this increases to almost half of all answers. So why do chat bots make stuff up? It’s because their training incentivizes answering every inquiry, whether they’re right or not. It’s an issue in fundamental logic. When training a large language model to perform well in competitions, what’s important is what wins, not what’s true. If you think of a quiz show where the only way to get points is to give the correct answer. You don’t lose anything by not guessing, but you also don’t lose anything from getting the answer wrong. Since there are no downsides to guessing, it is always in your favor to attempt answering – and bonus points if you convince the host you’re right anyway.

This is the game that AI is designed to play within. Over a million iterations, such a system would learn to speak smoothly and confidently, even when it’s unsure.

In a recent paper in collaboration with Georgia Tech, OpenAI (who makes ChatGPT) stopped framing hallucinations as a surprising fluke, but rather as an inevitable outcome of “natural statistical pressures” – what might be called “statistical destiny.” So when you combine humans and AI, you get even more overconfidence and deceptively persuasive answers.

Reinforcing these findings further, there was a new Stanford paper that coined the term ‘Moloch’s Bargain’ for what happens when large language models start competing for attention, sales, or votes, and the results were striking (though perhaps if you’ve followed this story, not surprising). It showed that for every gain in the model performance came an even bigger loss in honesty. In effect, more deceptive marketing, more disinformation in political campaigns, and more fake and harmful social media posts.

As an aside – not one I enjoy thinking or talking about – I worry a lot about the merger of AI with military capacity. I’ve been informed by people who are in a position to know that we’ve actually avoided a dozen, or perhaps even more, potential nuclear wars in the last 50 years. Most of these near-misses were avoided because at the time a single human was unsure and they chose to hold off until they had more information. If LLMs are trained on worst-case possibilities and gain control of these defense systems, the rational speed bumps of uncertainty and waiting that come from the gut-feeling of a human might disappear. This is one of the few things that keeps me up at night.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably aware that this is not just an AI problem, but really a mirror into our cultural values and behaviors – because we train ourselves the same way. As I mentioned before, social media emphasizes confident clips, companies promote decisive talkers, and politicians prioritize simplicity and easy to understand things over truth and complexity. In the context of the human predicament, economists tell stories of infinite growth, and that technology will be able to solve any challenges along our way.

Ultimately, the result is human hallucination. The cultural stories we tell ourselves, which then guide our actions, wildly outpace our energy, ecosystem, and time constraints. And then we’re shocked – shocked – when reality shows up to stare us in the face and remind us that infinite growth is not possible in a finite system.

The Deeper Costs

How do the costs of overconfidence actually manifest in society? People following this platform are well aware of the modern costs of overconfidence and certainty on the ecological side – and still we seem to discover more and more impacts every year. But beyond the environment, we can think of examples like the Challenger Space Shuttle launch: managers waved off the engineers’ concerns about the O-rings and low temps, and it resulted in seven lives lost.

(By the way, I watched this live at Kronshage Hall at University of Wisconsin when I was at college. It’s strange how the amygdala hangs onto these little emotional memories during the lifespan of a human brain.

Another well known example is the housing bubble that led to the 2008 Great Recession. Ratings and models said this is safe leverage, and optimism said ‘let’s party,’ while the few voices who dissented and called for caution were ignored. Cue: global crisis.

And again with the oil rig, Deepwater Horizon, which took shortcuts that looked efficient until they weren’t, leading to one of the largest oil spills in history and eleven lost lives. Governments also do this all the time, overpromising on the timeline and budgets of big projects, which eventually morph into years of delays and overruns. Challenges are normal, but it’s the overly optimistic baseline at the beginning which is the mistake. This is a repeating pattern in our culture. Certainty beats caution, and the costs come later.

… And the costs come later.

(“And the costs come later” might actually be a good mnemonic tagline for homo sapiens. Unfortunately, ‘later’ is arriving sooner than many of us think.)

Overconfidence in the Human System

One could argue that overconfidence and lack of caution is one of the core underlying drivers of the maximum power principle, which itself is underpinning global human ecological overshoot and the impending great simplification. (In fact, I may dedicate a future piece entirely to this concept). In some ways, this story seems to dovetail with Dark Triad personality traits – especially psychopathy – which is also worth pondering more.

But our predisposition towards certainty can be overruled by a trump card, which is self-introspection, learning, and the fast pace of cultural change.

To start, in my opinion, the mere act of saying “I don’t know” shifts the dynamic back to curiosity and the possibility for change. It re-engages our prefrontal cortex and it makes cooperation with others easier because we’re no longer defending an identity whose scaffolding was certainty. If you can’t admit that you don’t know, then you can’t really hear anything else.

Admitting uncertainty lets us engage in experiments, instead of arguments, and it creates room to develop scenarios. More importantly, uncertainty extends conversations with people who we might otherwise not talk to because we think we disagree from the start.

Can We Embrace Uncertainty?

So how do we put this into practice? I’m tempted to say, “I don’t know” and end this essay here, but – out of the desire to not just highlight a problem and then say goodbye – the following are some directional ideas.

Some guidance might come from the world of AI itself. In their aforementioned Why Language Models Hallucinate paper, OpenAI proposed a fix to hallucinations, not in the form of more data or a larger computer, but merely through changing the “benchmarks of success” when training models. This would be done by penalizing confident inaccurate answers more than when an AI admits uncertainty, and even giving partial credit for “I don’t know”. This idea originally comes from changes in the way standardized tests are graded in order to disincentivize blind guessing. If this works, and confidence thresholds are added to calibrate behavior, the hope is that models will stop bluffing – aka ‘hallucinating’ – when they’re uncertain.

This idea is really encouraging, but the caveat is whether the customers of OpenAI themselves will miss the model that gives persuasive, confident answers, and move to another model that delivers the desired ‘certainty porn.’ Regardless, it’s a shift in the right direction. I wonder what would happen if our society did the same?

What about us as individuals? It might be helpful to start by looking within. Try to notice when you’re giving an answer that you don’t fully understand or know to be a little untrue, and call it out to yourself and fact check it.

(I like to imagine a little Nate on my shoulder to voice these things to – perhaps you have a little Kathleen or little Joe or little Fang Li or whoever is reading this).

By doing this more with ourselves, it might help us get in tune with our gut feeling. By listening to the little part of you that says “Something is off with this story,” it may become more and more accurate and sensitive to when others are trying to sell you something that’s only half baked.

Something I’ve discussed in a previous Frankly is thinking in probabilities. The added twist here is to consciously calibrate the probabilities of your claims and then score how accurate you are. It might be as simple as, “I think there’s a 10% chance it snows this week, 30% next week, and 60% by next month,” and then see how you do when reality arrives. Of course, this practice risks triggering a collective action problem if you’re the only one in your network doing it. But, if a lot of people do this, I think it would be helpful.

And then there’s the somewhat well-known concept of Red Teams, which make dissent and uncertainty a formal role in any scenario, as opposed to a risk.

This can look like a designated person who plays ‘devil’s advocate’ to flesh out any weak points in a plan or statement. It might be helpful to then rotate whoever is tasked with being the skeptic, and to even thank these people publicly for playing that role on your team. This could be at work, or even at your community board meeting or your family check-ins. Rewarding uncertainty feels counterintuitive, but if it works for machines, maybe it could work for us.

Conclusion

In today’s society, we’re assailed from all angles with social and environmental problems, information overload from 24/7 internet access, and endless dopamine hits from gambling, pornography, shopping, and ever-increasing AI content – our minds are constantly full.

All of this excess is moving us further and further away from the cultural ability to express “I don’t know,” because we want the ease of a straightforward, decisive answer.

If someone is on the news, testifying to Congress, or is being publicly asked for the answers to our financial or ecological problems, replying, “I don’t know, but I can find out and get back to you,” would result in quickly being replaced by someone with a pithy, witty, or confident answer. And with all three, they’ll be branded an expert and invited back. The uncertain, careful answer – in today’s world – implies weakness rather than wisdom.

So what is the answer? I don’t know. But I suspect if we’re able to change how we keep score for ourselves, at home, at work, in the media, and especially in discussions about the future so that truthfulness and humility are as important as knowing the answers, I expect our systems would naturally get smarter and kinder.

What if those three magic words aren’t the end of the sentence, but the start of learning?

Thank you, talk to you next week.

Want to Learn More?

If you would like to listen to or watch the original Frankly that inspired this essay, you can do so here.

If you would like to see a broad overview of The Great Simplification in 30 minutes, watch our Animated Movie.

If you want to support The Great Simplification podcast…

The Great Simplification podcast is produced by The Institute for the Study of Energy and Our Future (ISEOF), a 501(c)(3) organization. We want to keep all content completely free to view globally and without ads. If you’d like to support ISEOF and its content via a tax-deductible donation, please use the link below.

Thank you, Nate. As a brand new high school teacher in the 1970s, I would extrapolate what I thought I knew in response to questions that took me to what I did not know.

High school students have great bullshit detectors. It took me about a year to grow into the "I don't know, but we can find out together" response, which the students appreciated, and which removed the inevitable anxiety that accompanies a fictional response.

Nowadays, "I don't know" is such a necessary response across disciplines.

Thank you for all you do to encourage both more knowing and the courage to admit when we don't.

Thanks Nate for the blog form! I think a couple more people I know would be willing to read your Frankly’s as blog posts.