Pruning for the Future

Loosening the Grip of Sunk Cost

This essay is adapted from last week’s Frankly video monologue titled “Sunk Cost and the Superorganism.” In the future, we’ll be adapting more Frankly videos to written versions and continuing to post them on Substack, so stay tuned for more.

Have you ever gone to a movie, realized it was terrible halfway through, and yet stayed until the end because you’d already invested time and money into it?

If so, this experience was an example of the macroeconomic behavioral dynamic called sunk cost, which I think has large implications for us personally and for our culture in the coming decades. Today, I want to talk about sunk cost not as just an economic term from textbooks, but as a real force shaping our lives, our homes, our careers, and the way civilization reacts to the Great Simplification.

What Is Sunk Cost?

By definition, sunk cost is any past expense – time, money, effort – that cannot be recovered. If we were totally rational as people, or as a species, logic would tell us that sunk costs should be ignored. We cannot regain any of what we’ve lost by continuing to spend more on that same thing. At the same time, continuing forward with the same past actions will only hurt us and make it harder to change course in the future.

Instead, if we were truly logical, we should make decisions based only on our present situations, circumstances, and expected future payoffs. Of course, this is easier said than done because humans have memories, emotions, and social status – all things that we’ve tied our sense of identity to. We protect past investments as if they were living things, as if they were literally us.

Sunk cost shows up in small ways all the time in our society: that previously mentioned bad movie we sit through, a huge meal we keep eating even though we’re full, or an expensive jacket we wear that’s a size too big. We might chuckle a bit at these examples because they’re familiar, and they seem pretty trivial in the grand scheme of things. But, if you apply this same economic logic to careers, romantic partners, home mortgages, or national infrastructure…the stakes become quite high.

When it comes to the human predicament, where (in the not-too-distant future) we will need to completely change the way society works, this sunk cost psychological phenomenon is one of the biggest speed bumps toward soft landings for our culture. We have built an entire way of life – roads, grids, suburbs, global supply chains, jobs, habits, status symbols, and identities – around an implicit expectation of more in the future. And even when we see the need to change, we hesitate because so much of what we see around us was really hard won – and it reminds us of better times, comfort, and stability. We want to protect it; we feel loyal to the ideals, life, and memories it represents.

Economists talk about sunk cost at monetary and financial levels: dollars, capital, and asset management. But there’s a wider boundary story. Yes, there are some costs in money and time, but there are also costs in identity, status, and expectations. Those last three matter more for our actions, happiness, and well-being than anything that checks out on a financial spreadsheet.

Sunk Cost in Our Identities

Think about how sunk cost has shaped your own identity. What’s the first thing you say when you introduce yourself to someone new? I would bet it’s something along the lines of:

“I’m an airline pilot.”

“I’m a professor.”

“I’m a podcast host.”

These aren’t only our jobs, they’re the stories that organize our lives. So, when reality around us shifts – costs of basic goods rise, AI changes the job market, degrees don’t guarantee jobs or higher income – the accompanying anxiety comes from more than just the economic threat. We also feel an existential threat to the way we define ourselves within the world. When we think about employment, we’re not just choosing between positions or companies – we’re choosing between versions of ourselves, which will also define how others see us. This all makes choosing wiser paths even harder.

Built Environments and Sunk Cost

In the environment around us, there are detached homes in the suburbs, highways with huge interchanges cutting through our cities, and gas stations that we’ve placed on almost every corner. All of this took many, many decades to create, using vast amounts of effort, steel, diesel, concrete, and finance.

All of this continues to work as long as energy is cheap, international peace enables just-in-time supply chains, the climate is stable, and financial and social cohesion are still functional. But as we recognize that those conditions are becoming more precarious, the rational response would be to stop doubling down on this system, and start changing course.

Even as this infrastructure continues to function, it requires the people living within it to sink more and more costs into expensive cars and fuel, making lower energy options such as biking or walking a more difficult choice. But sunk cost whispers to us, “What?! We already built it – look at all the money and materials we used – we have to continue to build, maintain, and support the infrastructure that we have.”

Lifestyle Choices

Sunk costs in our households come in the form of mortgages, school choices for our children, social circles, et cetera. Downsizing or relocating might actually make total sense in terms of energy and money, but it doesn’t pencil out in identity and relationship terms.

(That’s why my garage is filled with gear I might use again, like my kayak – which my girlfriend reminds me I haven’t used in eight years.)

In our communities, sunk costs in city budgets mean we assume a certain tax base and service area going forward. Streets, sewers, and pipes have to be maintained whether they’re at capacity or only half-used. This is despite the fact that the rational response to declining revenues or populations would be to retire some of this infrastructure, cluster services together, and repurpose land. These things make more sense ahead of the Great Simplification (rather than after), but sunk costs at the local aggregate level resist all this. There’s no mayor in this country that wants to be the one who “shrunk the city,” even if it improves citizens’ quality of life.

A local example that comes to mind in Minneapolis is the recent discussion of what to do with the aging, below-grade Interstate 94, which cuts straight through the Twin Cities. This was a massive project to build out, and it cut through many neighborhoods. Now it’s at the end of its lifespan.

Many of those who would like to see lower-energy alternatives advocate for completely filling in the highway corridor, and returning it to neighborhood streets, making it more walkable and bike-able. But the psychological sunk costs of the original project – and the habits and lifestyles that were built around it – have prevented that option from remotely becoming a reality.

Stories We Live By

We’ve spent a century or more selling a story that progress is synonymous with more material throughput, more individualism, more convenience, more square footage, more speed, more gadgets, and more money. That story is a sunk cost as well.

Yet, there are millions of careers, tons of institutions, and a whole entertainment industry reinforcing that story. Today, there are seedlings of a different story – one of ‘enough-ness,’ or what’s called lagom in Sweden, or sobriété in France – which center on repair, reuse, maintenance, and local resilience. But this alternative narrative rubs against the deep emotional grooves of the progress narrative that is ‘sunk’ in our psyches. People, including many followers of this channel, can agree with the facts of reality, and yet simultaneously still feel a loyalty to their own past, and the future they had planned their life around.

Narrative emanates from storytellers – and right now our cultural storytellers are economists and techno-optimists, who are largely energy and systems blind. The receding horizons of energetic remoteness, in effect the depletion of our fossil energy bank account, provides an additional slant on sunk cost in that we increasingly will not have unlimited do-overs.

One central thing that economists miss is that large-scale game moves are finite. Because they’re fire-based, there’s only so many of them, and they’re also costly to our planetary health. As such, the new infrastructure that we sink our costs into today is a very limited opportunity to build what will be useful for the future. Will people be able to build a Hoover Dam in 100 years? What about 200 years?

Leveling the Playing Field

To help make this idea feel more real, I’d like to offer the following thought experiment. Imagine that everyone on Earth was magically put into safe, temporary stasis for a year. We all wake up healthy at the end. In that year, our houses vanish. Every mansion, condo, and apartment is gone. Instead, there are durable, weatherproof canvas tents – all in the same basic footprint, many different colors, set up in communities across the country. All the essential services still function: water, sanitation, heating, and basic power. No one is homeless. No one is singled out. Everyone is living simply, but not necessarily equally, because there are many other aspects to our lives. But at this moment, where we sleep is all the same.

What happens next? Of course there are exceptions, but my bet is that many of us would exhale. Many of us would feel a sense of relief by letting go of the expectations of the past; of the lifestyle we thought we wanted and worked so hard to have, but that wasn’t actually as rewarding as we thought it would be. We bought into cultural ideals. We put in the work, and bought all the things we were supposed to want. Yet somehow, in many cases, we’re still left feeling dissatisfied, empty, and lonely.

This tent thought experiment relieves the pressure of having to choose to let go of that particular sunk cost. It relieves us of the pressure to ‘keep up with the Joneses,’ which I think might be a quarter or a half of the reason for our modern exhibitions of material grandeur. In this alternate world, the comparison treadmill would quiet down. We’d look around and realize a lot of our drive for more stuff wasn’t really about the stuff – it was about continuity and keeping our current life going because it’s ours, even if we don’t love it. And it’s about status: keeping up with neighbors and colleagues in regards to what our culture tells us matters.

From a biophysical perspective, the tent example reveals how much of our resource demand, which is completely unsustainable at current levels, comes from maintaining the inheritance of our past choices. When that inheritance resets, i.e. from mansions to tents, a surprising amount of material desire might reset with it.

Of course, we’re not going to wake up in tents. The point is to notice the psychological weight of sunk cost and how much it shapes what we want. It explains a fair part of why transitions feel so hard, even when the new path might be cheaper and systemically wiser. We’ve become attached to our specific arrangements. In fact, the arrangement has actually become the thing we value.

A related thought experiment happens when you ask the question, “What are the things you would do if everyone else suddenly did it too?”

I think there’s a category of things you would never do, even if everyone else did – like eating cat poop, which I call Almond Rocas when my dog grabs them from the litter box. Personally, I’m never going to do that.

There’s also a category of things you would do, even if nobody else did, like walking in a gentle rain in an old growth forest or staying up late to see the Aurora Borealis, two things I’ve done recently.

There’s a third category – what you would suddenly consider doing if everyone else did – which underpins our current cultural momentum and metabolism. This would be a long list of things because, in my opinion, we humans are way more socially constrained than physically constrained (at least once basic needs are met). I’ll likely do a future Frankly on that topic to unpack it more, and leave it at that for now.

Practices to Shift Perspective

So, what do we do? How does this sunk cost dynamic play out in the Great Simplification? There are a few practices – personal and cultural – that I’ve considered this past week, which may help to loosen the grip of sunk cost without pretending that it doesn’t exist.

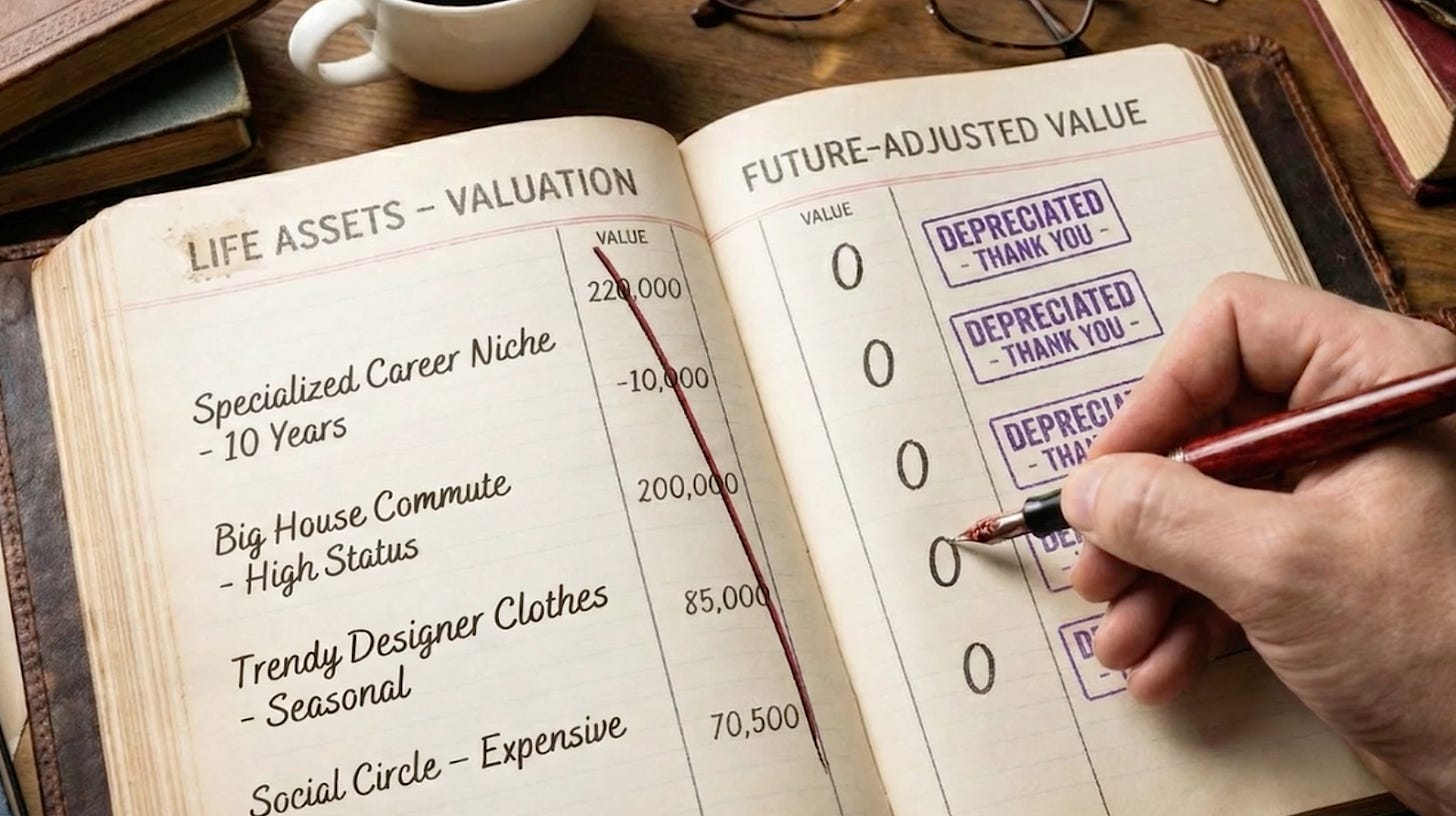

Hold a “write-down” ritual for identity. Businesses write down assets when conditions change, they write off what has become dead weight or doesn’t work anymore. Individual humans might do the same. Name the roles and purchases that served you well and thank them, then explicitly lower their book value in your mind. This might look something like: “I invested a decade in this path. It gave me skills and friends and status. The world has now shifted. I’m releasing that part that no longer fits.”

You might also separate use from symbolism. Much of our stuff serves a symbol: competence, belonging, success. Try replacing that symbol with a practice. If the truck you own tells you that you’re handy, but you don’t actually use it very often, keep the handiness as a practice while you sell the truck. You can always share or rent one as needed.

Pre-commit to a future of friendly defaults. Decide ahead of time that your next home will be smaller. Your next appliance will be of the repairable type. Behaviors like this allow your neocortex today to trump your amygdala of the future. If you must spend, put your dollars into flexibility and optionality: buildings that convert uses; streets that can shift use from cars to bikes to buses; local microgrids that can run independently during blackouts; careers and skills that are easily transferable instead of hyperspecialized for an industry niche.

Tell new stories about status. We are social creatures, and that’s not going away. The pursuit of status is a part of being human. So shift the status. Hold the neighbor who repairs, mentors, plants shade trees, and bikes in high regard. Celebrate and congratulate the local school that chose to renovate an old building instead of building a new fancy one at the edge of town. I think status will be an antidote to sunk cost like nothing else.

Lastly, practice the tent or cat poop thought experiment together in a local meeting or classroom. Ask: If we all woke up in sturdy tents, what part of our old lives in this community would we rebuild first, and which parts would we let go? What would I stop doing if everyone else has stopped? And what would I start doing if everyone else started? I think the answers might surprise you because they would surface the real wants that were beneath inherited wants. That clarity could be something quite informative and valuable.

I think some people will claim that the way I’m suggesting to jettison the sunk costs, infrastructure, and all the things is akin to giving up. I would actually argue the opposite. We are now in a risk-adjusted asset management for a living civilizational phase of our culture.

We acknowledge what we’ve built. We honor its service. We see what’s working, and what’s not. Then we steward the transition to designs that can actually last in the hotter, less materially intensive, more volatile coming days and centuries.

Of course, the opposite is generally happening, as we see states like Florida erase all mentions of climate change from their laws… because much of the state will literally be a sunk cost in the future, and mentioning it will screw with the property values.

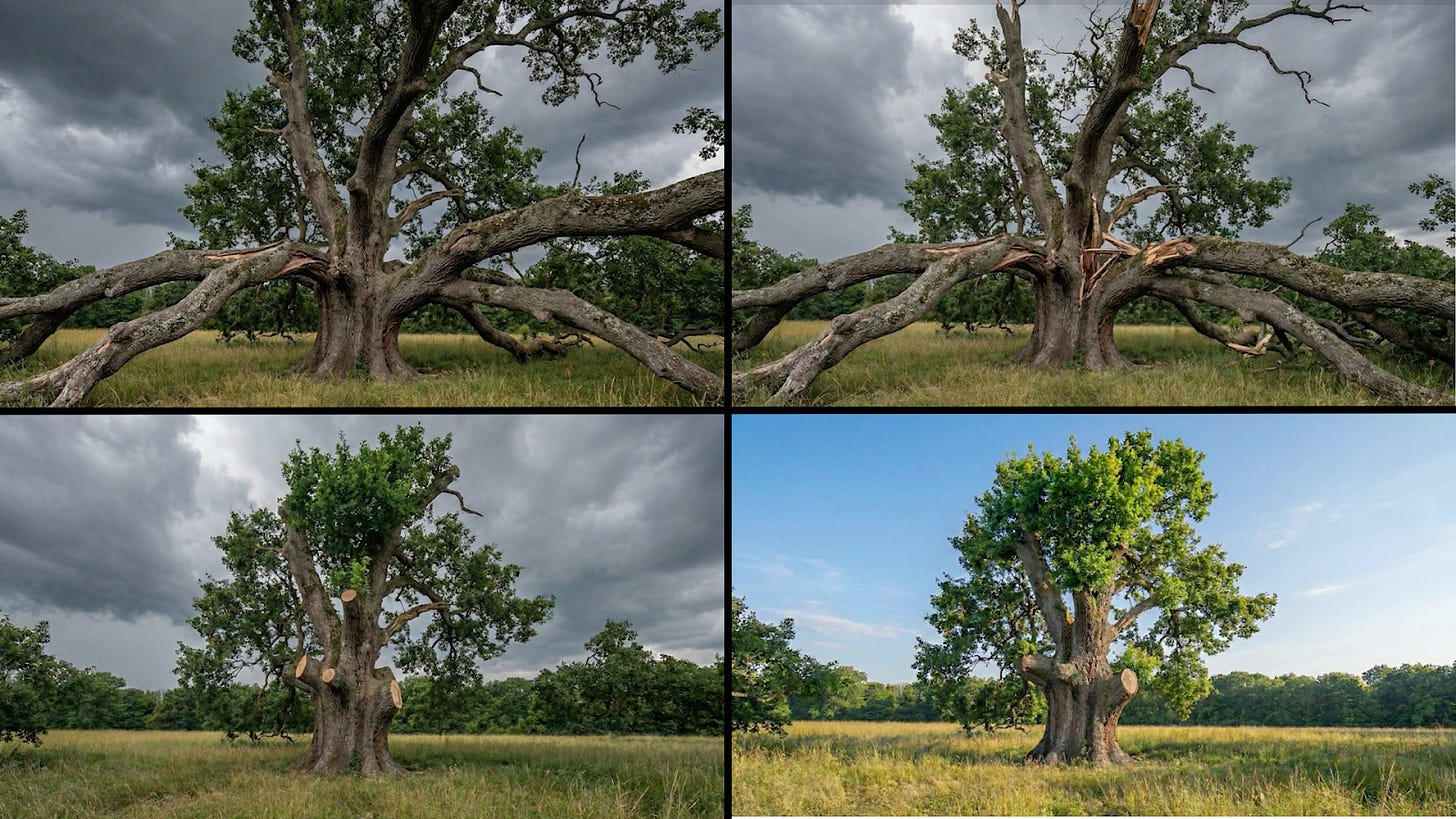

Pruning for the Future

For a closing analogy, picture an oak tree. Decades ago, someone pruned it badly and the tree responded by growing strange, heavy branches at awkward angles. Those branches are sunk costs in wood. If we keep letting those branches grow, the tree will eventually tear itself apart in a storm. A good arborist will study the structure, make careful cuts and lighten the weak points in order to guide the new growth in stronger directions.

Yes, the tree will end up being smaller and less majestic than the full canopy we remember. But it will still be beautiful, more stable, and now capable of another 50 to 80 years of life (including all the gifts it provides us humans).

The people subscribed to this channel are now the arborists. Our past decisions are in the grain of our cultural wood, and while a few can be braced, some of the branches have to go. But there’s new growth already sprouting: in community gardens, maker spaces, repair shops, bike lanes, libraries that double as social organizing spaces, and in so many other places.

Each of these choices turns down the volume of sunk cost and how it grabs at us, and increases our optionality for an uncertain future. If we can learn to say “thank you” to the paths that brought us here, but change course to the ones that can carry us forward, I think we’ll find the coming transition is less about loss, and more about reclaiming agency. And maybe – just maybe – the canvas tent version of us shows up in spirit: lighter, less jealous, less stuck in the life we thought we wanted, more neighborly, and more free to focus on the parts of life that actually feel like life.

I made this Frankly for those subscribed to this channel, but also for myself, because speaking about this brings me closer to actually addressing this in my own life.

Thanks for reading.

Want to Learn More?

This essay is adapted from a previous Frankly video titled “Sunk Cost and the Superorganism.” In the future, we’ll be adapting more Frankly videos to written versions and continuing to post them on Substack, so stay tuned for more.

If you would like to see a broad overview of The Great Simplification in 30 minutes, watch our Animated Movie.

If you want to support The Great Simplification podcast…

The Great Simplification podcast is produced by The Institute for the Study of Energy and Our Future (ISEOF), a 501(c)(3) organization. We want to keep all content completely free to view globally and without ads. If you’d like to support ISEOF and its content via a tax-deductible donation, please use the link below.

It’s so good to find some suggestions for how to apply the theory— thank you.

Very pleased to learn you will be converting podcast material to essay form, as some of us are confirmed readers who eschew screens wherever possible.

The social contract is so important to us, isn’t it? In our own lives, as adults, my husband and I are more willing to break from the contract than many. Where we struggle is in regard to our children. As they grow older and need to navigate their own social lives, it becomes harder to stick to our ideals rigidly. And I think that’s ok, but it’s definitely something I’m very conscious of and think about proactively.

I’m trying to balance our choices there, sticking to our ideals as much as possible but not to the point where we cause our children to feel ostracized and then lead to a bitterness in them. I’m trying to give them the confidence and intellectual & spiritual grounding to be confident in departing from dominant culture, but retain the ability to integrate when and how they desire. It’s tricky, and I’m sure we don’t always get it right.

And then, that question in and of itself speaks so highly to the importance of developing supportive social networks. We don’t all need to agree 100% on every issue, but we need aligned social networks that make it easier to walk down new pathways. I’m grateful to have largely built that in my own life.