Why Does Everything Cost So Much?

The Forces Behind Inflation and Deflation

This essay is adapted from last week’s Frankly video titled “Inflation, Deflation, & Simplification.” In the future, we’ll be adapting/updating more Frankly videos (current and historic) to written versions and posting them on Substack, so stay tuned for more.

Tens of thousands of years ago, in what’s now known as Tanzania, our ancestors’ price signals were gazelles, tubers, fruit, and other real, tangible goods. Today, our prices are the numbers listed on rent, groceries, tuition, and gas – small barcodes everywhere asking us, “Yes or no?”

How often do we ask ourselves why that number is there? What forces helped to shape what appears on the price tag?

As Milton Friedman famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” This is true. The amount of money created with respect to the economy is important, but prices in dollars (or euros, yen, rupees, etc.) represent signals from a living system that has thresholds, feedbacks, and delays. Money acts as a current in the ocean of energy, materials, technology, leverage, ecosystems, and social contracts. Ultimately, money itself is a social contract that relies on trust and shared values – a contract that will be increasingly stressed as a Great Simplification scenario approaches.

There is a wider boundary framework of how all these economic factors interrelate. In this essay, I outline eight major drivers of either inflationary or deflationary impacts on prices.

What is Money?

In order to unpack prices and the factors that influence them, first we have to understand what money is, and what purpose it serves within our society.

Economic textbooks will define money as:

A unit of account

A medium of exchange

A store of value.

This is all true. But a biophysical lens adds that money is also:

A claim on energy

An externalization of ecosystem costs such as pollution, deforestation, and species extinctions.

When spent, every dollar hires an invisible energy worker that leaves a biophysical footprint.

This leads us to ask the question: How much spendable money can realistically exist in a functioning world?

How is the Amount of Money Determined, & How Does This Affect Prices?

Money creation is the most obvious driver of inflation. When commercial banks issue new loans, they create a new deposit of money. In parallel, when central banks and treasuries coordinate stimulus, they inject new purchasing power into the system.

When we look at the history of indicators of broad money supply – M1 and M2 – we see long periods of steady growth punctuated by spikes, usually around financial crises. This money supply growth has more or less tracked with our expanding throughput of energy and materials. More money begets more stuff, which enables more credit growth (and again, more stuff).

But when credit expands more quickly than the real economy’s capacity to deliver goods and services, people’s purchasing power outstrips the amount of things that are actually available to buy. Therefore, prices rise to match this relatively increasing scarcity.

Often in crises (and sometimes not in crises, like now), it’s the central banks that pour on this accelerant. Low interest rates and asset purchases lift financial wealth, which then spills into real-world demand with a time-lag. Interest rates can also be considered a “price.” They’re the price of money. Lower interest rates (i.e. a lower price on money) increases demand for money and pushes prices for everything else higher. In turn, higher rates lower demand for money, shrink money supply growth, and decrease demand for other goods and services, pulling prices down.

So the first category – money creation – has an inflationary impact on prices. Indeed, the purchasing power of a U.S. dollar has declined by 95% in the past century. That’s the impact of inflation.

Role of Resource Depletion

The second category, which those of you who’ve watched my online presentations might see coming, stems from the fact that we can print money, but we cannot print energy. We can only extract it faster.

The modern economy depends on concentrated ores, fertile soils, ample fresh water, and above all, dense and affordable energy. As high-grade resources are used up, we go after thinner, deeper, more scattered deposits like shale oil. That means more trucks, more rock moved, and more energy burned per unit of output.

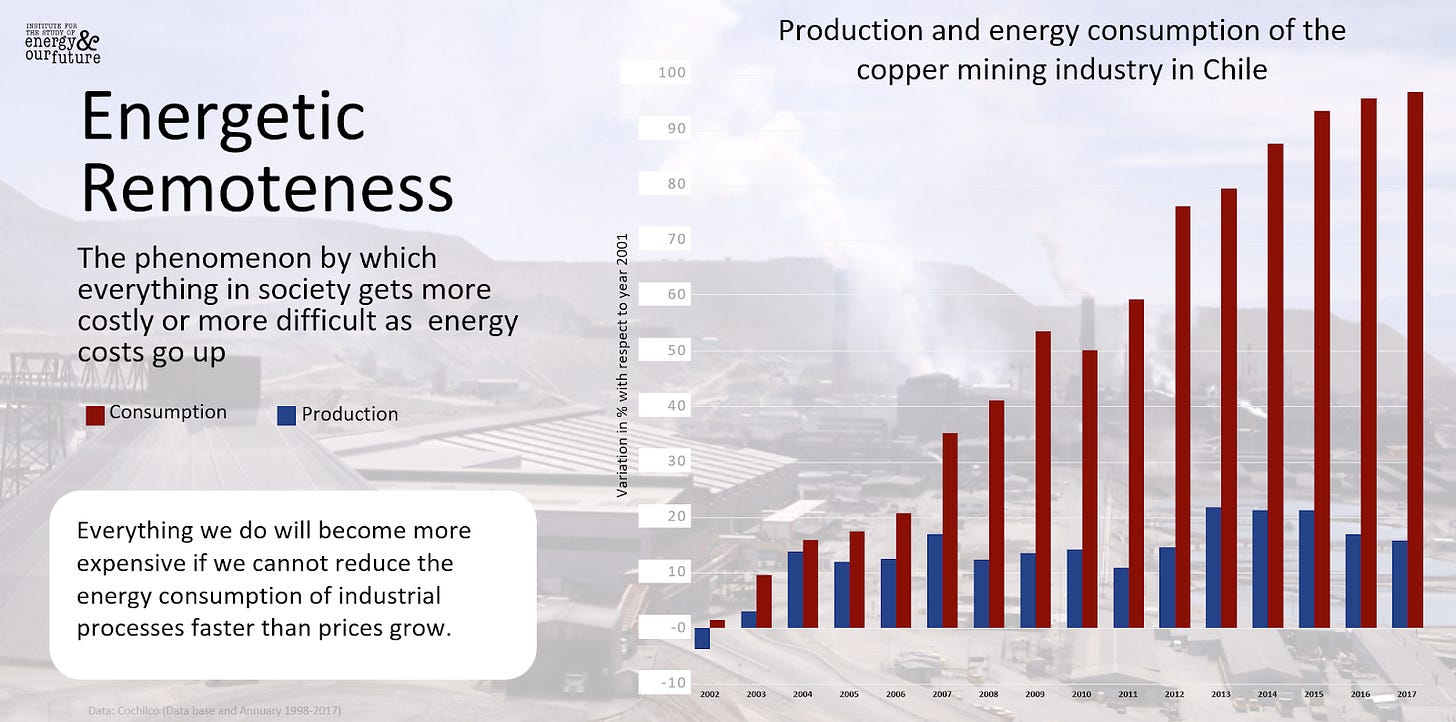

Back in the 1800s, we used to mine 40% copper ore in Butte, Montana. A little over a hundred years later, in 1920, copper ore was concentrated at 4% for the entire country. Today, copper is down to 0.4% of the rock it comes from…meaning that we have to grind up 10 times more ore to get a kilogram of copper. That’s happening to nickel, oil, soil, and all other kinds of resources as well.

We can see an example when looking at copper production in Chile. In the graph above, the blue bars represent copper ore production by the entire country. The red bars show how much energy was needed to get that ore.

This dynamic is inflationary. When it costs more to obtain and process the raw resources, the prices of the end product inevitably goes up. Because energy is embedded in all goods and services, everything in society will get more expensive if we can’t reduce the energy consumption of industrial processes faster than energy prices grow. Natural resource depletion, writ large, is also inflationary.

Technology and Productivity

Technology is usually deflationary. Over time, when processes become repeatable, like the creation of computer chips, we reduce costs due to learning and new innovation. We squeeze out waste, become more efficient, scale production, and standardize processes.

A television today costs a fraction of one from 20 years ago, despite the fact that it also has more capabilities and complexity. As a result, demand for televisions has also increased exponentially. Today, nearly every household in the U.S. has at least one in their homes.

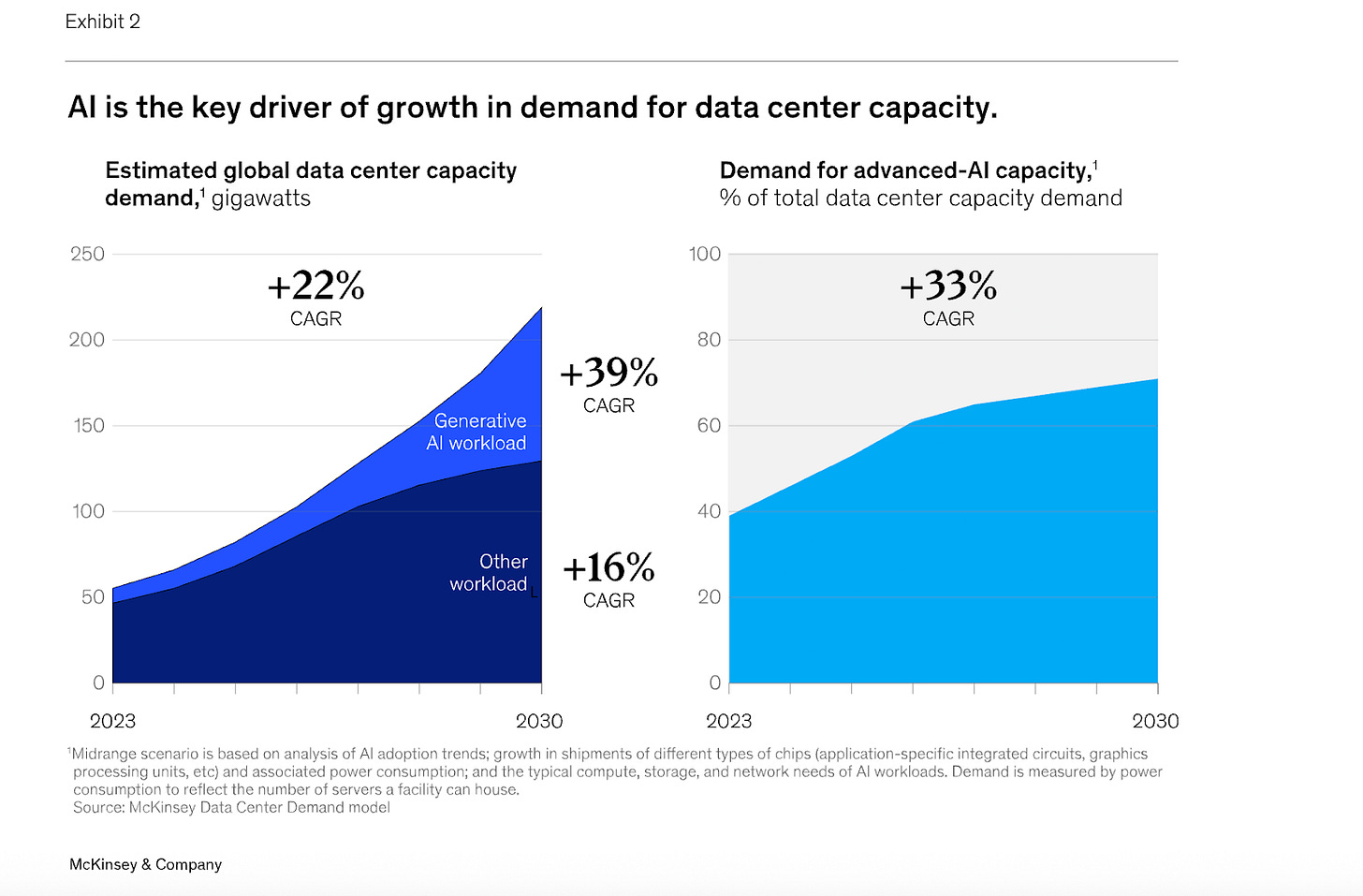

But not all technologies reduce prices. Some shift the costs into the physical world. A current example is Artificial Intelligence. Inference and training demand large, always-on data centers. These require electricity, land, cooling, chips, and the supply chains behind those chips. If power grids strain – or if adding capacity requires expensive gas peekers, long-distance transmission, or critical materials – AI’s upstream footprint can cause prices to go up.

In turn, it’s expected that utilizing AI in the broader economy might increase overall productivity by 1-2% per year, which would be massive if it happened, but a mixed bag with respect to impacts on overall inflation.

So technology tends to make replicable things cheaper until it collides with resource limits or shifts costs to energy-hungry infrastructure. But at least historically, technology has been deflationary.

Not Just Prices, Affordability

Prices aren’t just about costs, they’re also about who is able to pay. Affordability is the anchor of demand for things.

As I’ve pointed out recently on this show, there’s a big difference between median income and wealth versus average income and wealth (especially in the U.S.). A lot of stories are appearing in the news about the ‘K-shaped economy,’ describing how the median household is really struggling and feeling the financial pinch.

So, it stands to reason that when large groups run out of financial dry powder, then wages lag, interest payments rise, and savings shrink… and people in these groups will cut back. Sellers find fewer buyers at yesterday’s price, inventories accumulate, and discounts appear. If we consider price as a meeting point, if the buyer steps back, then the price goes down (or deflates).

We saw this in various sectors after the COVID-19 stimulus faded: used car prices dropped, certain consumer goods piled up, and rents were being negotiated where vacancy rose. Affordability is why the “market price” is not a static thing. Price is just the agreement between buyers and sellers.

This is why inequality is ultimately critical to the continuity of socioeconomic systems – because if a third to a half of the population can’t afford basic things, the financial system itself would collapse. Broad lack of affordability is deflationary. We haven’t seen it for a long time, but it’s on the horizon.

Leveraging and Gearing

Greed, status, and human social creativity adds invisible springs and gears between the real economy and the prices we see. Leverage, which uses borrowed capital to invest and hypothetically make more returns than the original loan, magnifies the moves in asset prices slowly on the way up, and often quickly on the way down.

Then leverage on leverage – derivatives, basis trades, carry trades – further intensify that magnification. So deleveraging is deflationary for asset prices first – stocks, bonds, houses, crypto – and can become deflationary for goods and services if the credit mechanism seizes up.

We’ve had loud, but so far not catastrophic, reminders of this. The unwinding of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 is an example. These were the guys, who I used to work with at Saloman Brothers, that forced massive margin calls in the global financial markets that weren’t about fundamentals; they were about our penchant to create much higher financial claims on reality than reality supports.

In April 2020, crude oil futures dropped to negative $35 per barrel, and stayed negative for over a day. This didn’t happen because oil became worthless. It was because storage was full, contracts were rolling, and leveraged financial players somehow created claims on this physical resource that were way bigger than the resource itself. So they had to exit because of the financial contract.

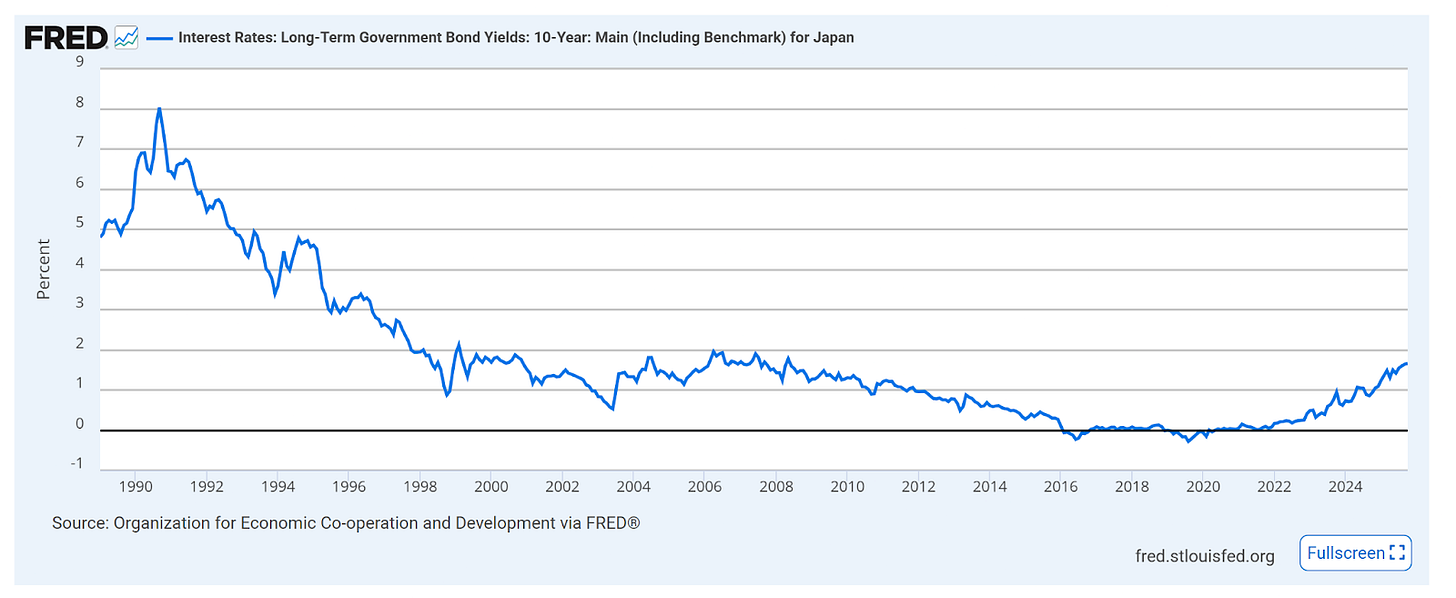

Today, one of the world’s biggest financial gears has been the Japanese carry trade, where international finance people borrow in Japan where interest rates are low and invest in places where rates or expected returns are higher in order to pocket the difference. This works…until it doesn’t. Due to the amount of leverage in the system, if rate differentials compress or the yen weakens, the resulting unwind can force selling in places that previously seemed unrelated (such as the $1 trillion worth of U.S. government bonds held by the Bank of Japan).

Ultimately, forced selling of previous leverage is deflationary for asset prices, and sometimes for real goods downstream if credit tightens. Looking ahead, leverage in our financial system has a potentially large deflationary impact on prices.

Underpinned by Ecology

We don’t often add ecology to the list of things that influence prices in our lives, but as we inexorably leave the stability of the Holocene, nature is no longer going to be an economic footnote.

Droughts and low river levels affect barge traffic and power plant cooling – not to mention hydropower and crop yields. Heat waves pull gigawatts towards air conditioning, straining electricity grids. Hurricanes in energy basins shut down refineries or offshore production. Calm, cloudy weeks in winter – what Germans call Dunkelflaute – cut wind and solar output just when demand is high. All of these things raise prices.

On top of that, more volatility means paying for buffers: inventory, backup generation, redundancy, insurance. These buffers are inflationary; they add costs.

There’s another, longer term, inflationary ecological layer as well. Biodiversity loss and soil degradation quietly raise input costs over time. Pollination, pest control, and water retention used to be free services from ecosystems. As services such as those fail, we tend to substitute them with more expensive energy and chemicals – and the impact of these substitutions shows up at the checkout counter.

Declining ecological stability in the 21st century will have an inflationary effect on prices.

Currency Reform and Hyperinflation

The container that holds all prices is the currency system itself. Currencies are human stories backed by power, institutions, energy, resources, but especially trust. Over long periods of time, those stories change. Pegs break, political agreements dissolve, and claims exceed reality.

Historically, most currencies have lasted about 30 years in unchanged form. When a currency loses credibility, the move can be quite swift. People suddenly shift en masse from prioritizing money, to prioritizing the things that money could buy. This is called hyperinflation – when the purchasing power of money drops so fast, it becomes close to worthless. Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, and Argentina are all different paths of this same arc. Often, after the rapid plummet of the existing monetary system, there’s a reset. New rules, new units, and new living standards emerge as the economy restabilizes and finds a new normal.

This reset can be sharply deflationary. We’re now 80 years past Bretton Woods, running a fiat system with deep dollar plumbing throughout the world. We’re also 50 years past the end of the gold standard, marking the end of any built-in tethers to physical foundations. That system has delivered flexibility and growth, but has also leaned heavily on assumptions about energy availability and affordability, geopolitics, and domestic cohesion. If those pillars wobble, trust in currency becomes something we took for granted.

I don’t know the timing or the form of any future reform. I do know that in response to our accelerating crisis, governments (like Japan) will increasingly look to borrow and spend their way out of tough economic situations. Eventually, instead of a “too big to fail” situation like in 2009, we’ll have a “too big to save” situation: no group of central banks would be big enough to bail out France, for example. Then, it’s the hedge fund known as the global human economy that will have a margin call.

Currency architecture is the driver of prices in a way most citizens never think about…until it’s the only thing we think about. When it happens it’s hyperinflationary, then the aftermath becomes deflationary.

Complexity

This entire list of things that influence prices is also a story of complexity.

Sustained economic growth has dramatically increased societal – and financial – complexity. When a system grows, we increase the nodes in a network of people, companies, or supply chains. When the nodes increase, the number of connections between the nodes increases by roughly the number of nodes squared and divided by two. So with ten nodes in a system, there are 45 connections. But at 50 nodes, there are 1,225 connections. The exponential nature of connections in society requires more and more energy to maintain, which has built webs upon webs of dependencies and interdependencies.

Why does this matter? Because what follows the increasing complexification of the last century is a simplification.

Given the amount of leverage, claims, built infrastructure, and energy blindness amidst cultural stories of singularities and ‘inevitable’ planet exploration…it will eventually result in a Great Simplification. And a core implication and warning from this platform is that complexity doesn’t do well in reverse.

Walking the Tightrope

All the forces outlined in this essay are starting to stack and influence one another. Governments and central banks have taken over a large portion of the money creation process, and nation states are now going into debt in huge and unsustainable ways.

Bond and currency markets are starting to pay attention to these trends. There’s currently an active move in Asia and the BRICS countries to move away from the U.S. dollar, which underpins the whole global financial system.

Japan’s interest rates, which have been essentially zero for the past 30 years, are spiking and the currency is selling off. Through a biophysical lens, Japan has no real natural resource endowment, requiring that it imports most of its energy with a suffering currency.

AI is accelerating demand for energy and water infrastructure. At the same time it’s replacing humans with robots and software – and these same humans have to pay for groceries, auto loans, or mortgages.

I also just learned that if you were to order a new natural gas combined-cycle turbine by General Electric today, it can’t be delivered for another 6-7 years due to an intense backlog. And lest we forget, oil depletion is accelerating. Peak oil has never been about running out of oil, rather that the open market oil that’s owned and sold by exporting countries wouldn’t be able to keep pace with the growth requirements of the world’s financial system.

We are in a perilous period where we are increasing our financial claims on reality, while reality deteriorates. AI is a huge wildcard. It might boost productivity, which likely won’t be evenly distributed, but it also might crash the system before it lifts off due to all the demands on energy, water, and other infrastructure.

How all of these things interrelate in the coming decades is impossible to fully predict. But, barring some new widespread boost in productivity, we are in a financial/social musical chairs moment. What money is, what it is underpinned and supported by, what it can be spent on, and how it holds its perceived value are all open questions.

As a central banker or head of government, walking the tightrope of inflation and deflation on the upslope of the Carbon Pulse was relatively straightforward. Now, this tightrope has become the social contract. Unless productivity rises and its gains are widely shared, we’re playing musical chairs with increasingly fewer chairs, and more people wanting seats.

The Mother of All Deflationary Pulses

Lastly, as followers know, I care the most about the natural world and its ability to support far-off future generations of humans and other species. However, between today’s predicament and a world where our species lives more in ecological balance lies the mother of all deflationary pulses. I’m calling it the Great Simplification, which is what we’ve been unpacking for the last four years on this show. It’s this deflationary pulse on the horizon that makes me skeptical of environmental and cultural solutions which assume, or require, current levels of societal complexity within a 19 terawatt (and growing) economy. Because, in my opinion, those plans are not going to make it when material throughput contracts.

There are going to be many financial stories and headlines in the coming years. The reality is that money is a cultural belief, and our current price tags are messages from the metabolism of our civilization.

But civilizations change. They go through phase shifts. One of the core inferences of this warning is the need for advance policy: understanding scenarios, building research, and “break glass in case of emergency” interventions that result in bending, not breaking. We have to catch the tightrope walker in a net five stories down, rather than allow him to fall 25 stories to his death.

It’s important to recall that at the moment of a Great Simplification scenario – a deflationary pulse – there will exist the same amount of factories, oil infrastructure, and expertise as before the fall. They just won’t make sense or be affordable anymore.

This is the story I’ll dive deeper into next year.

Thanks for reading.

Want to Learn More?

This essay is adapted from a previous Frankly video titled “Inflation, Deflation, & Simplification.” In the future, we’ll be adapting more Frankly videos to written versions and continuing to post them on Substack, so stay tuned for more.

If you would like to see a broad overview of The Great Simplification in 30 minutes, watch our Animated Movie.

If you want to support The Great Simplification podcast…

The Great Simplification podcast is produced by The Institute for the Study of Energy and Our Future (ISEOF), a 501(c)(3) organization. We want to keep all content completely free to view globally and without ads. If you’d like to support ISEOF and its content via a tax-deductible donation, please use the link below.

Thank you for adapting your “Frankly” content in this way. I feel like this allows you to expand and deepen your inquiry even further.

I will add that the factories, oil infrastructure, and so-called expertise we have now is already makes no sense in relationship to resilient relationship - or human survival. Our current human-built infrastructure exists to further concentrate wealth and power within the human-built infrastructure by stripping the planet and masses of living creatures — including people — from the earth. Our current civilization is ecocidal and genocidal, and is completely resistant to transformation.

Orwell noted that political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

We are too polite to say it, but we have created what Britt Wray has called “bubbles of uncare” (see Generation Dread) that preclude the very transformations that we need.

We are dying of politeness as we refuse to name the simple reality that the Dark Triad ensures that we are - and will - accelerate ecocide and genocide until the self-terminating process is complete.

We are well into this rapid, anthropogenic extinction event.

We do not control this process. We wealthy white people are not even capable of asking the right questions yet - let alone responding with wisdom.

My own response is that we can best respond by creating localized communities of care as we ride out the process of accelerating extinction.

This is not the only answer or even my final formulation, but rather a working idea about how to look around in the deluge, and celebrate in a good way while letting go of outcomes.

I hope you will continue to mention the Dark Triad, and also explore the way that our entire civilization has been shaped to form a profoundly malignant “bubble of uncare” that reduces our boundaries of inquiry so that we hide our real relationship to the world from ourselves.

Some time ago, I read an article in which a young Canadian Anishinaabe woman simply said: “you want my baby dead.”

I think she was right. We really don’t care enough to know, and so we don’t bother inquiring deeply into what we need to know in order to care. This lack of empathy drives our self-terminating pattern of futile “taking without regard”.

I suggest that empathetic inquiry is the only true science, and that we have abandoned it completely. We are interested now only in developing ecocidal and genocidal technologies. War and other organized crime pay very well. Everything is connected.

I write this as a simple honest response in this moment, and intend it as constructive critique rather than as any kind of despair aging remark.

Our crisis is profoundly spiritual and relational in nature. The key question facing each of us is really how to be loving in. The brief flash of time we are here.

I do suggest that we attend to the reality that we humans - and especially those at “the top” of our current corrupt, malignant civilization — have never been in charge of evolution, note will we ever be in charge.

We are here to love. Nothing more. Nothing less. Nothing else.

We already bear witness to the dying throes of a mad civilization. (I suggest that this is happening now - not maybe going to happen. I think you essentially agree there?)

Our question is how to be of loving service as changes happen that we do not control. That moves to the question of just what do we control?

My sense is that our technological solutions will simply deepen and amplify the damage done to the biosphere. And yet no one wants to talk very much about changing how we live. Once again - the “bubble of uncare” prevents the very empathetic inquiry we need most to be making!

I ran across this quote from Kurt Vonnegut - which I think you will deeply appreciate:

“I have a message to future generations: please accept my apologies, we were roaring drunk on petroleum.”

Warm regards, and encouragement that you keep on going deep with your work!

Money is the key factor in all of economics...and the present anomalous monopoly monetary paradigm for the creation and distribution of all new money is Debt Only. Historically, every new paradigm has always been in complete conceptual opposition to the present paradigm which indicates that the new monetary paradigm that breaks up the monopoly paradigm of Debt Only is Strategic Monetary Gifting. Find the most efficacious points in the economy to APPLY the new paradigm and...away we go!

New paradigm CONCEPTS are synonymous with Wisdom insights in that they are deep resolving simplicities. EVERYONE AND EVERYTHING IN THE TEMPORAL UNIVERSE is effected by the monetary paradigm because it is the tool for action or the reason for inaction in the economy that EVERYONE MUST PARTICIPATE IN TO SURVIVE. This summary enlightens the key factor for the greatest SIMPLIFICATION presently needed to effect The Great Simplification.